By Jean Blish Siers *

According to a recent report by the Urban Institute and the University of Illinois, in Mecklenburg County, where I live in North Carolina, the average cost of a buying groceries and preparing a meal is $2.44. (See the very cool interactive map here.) In Charlotte, Mecklenburg County’s largest city, that feels like a pretty good deal compared with eating out. We’re fortunate to have a wide variety of restaurants here where a meal can run you anywhere from $5 for a fantastic bahn mi sandwich to a hundred dollars for a fine farm-to-fork experience.

According to a recent report by the Urban Institute and the University of Illinois, in Mecklenburg County, where I live in North Carolina, the average cost of a buying groceries and preparing a meal is $2.44. (See the very cool interactive map here.) In Charlotte, Mecklenburg County’s largest city, that feels like a pretty good deal compared with eating out. We’re fortunate to have a wide variety of restaurants here where a meal can run you anywhere from $5 for a fantastic bahn mi sandwich to a hundred dollars for a fine farm-to-fork experience.

But based on this report, it isn’t good news for the thousands of our citizens who rely on Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which many of us still know as food stamps. The study found that a household receiving the maximum SNAP benefit each month receives $1.86 per meal. The report’s authors found only 22 counties in the entire United States where the cost of living and food prices would allow someone to buy a month’s worth of groceries with their SNAP benefits.

My neighbors’ benefits in Charlotte fall 31% short of the mark. Other counties fare much worse. In rural Crook County, Oregon, which relies on agriculture and forestry for jobs, the average cost of a meal $4.39, or 136% more than the SNAP allowance. And in urban Manhattan, where one-fourth of all SNAP recipients live, it costs $3.96 to buy food for a meal, or 113% more than their benefit provides.

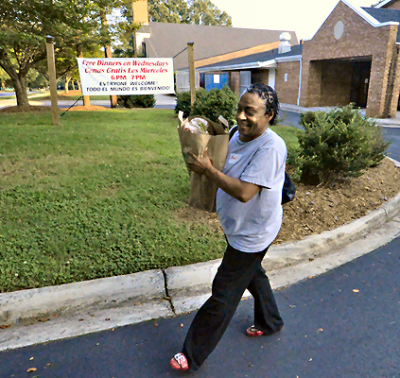

What does this mean? It means that almost every SNAP recipient must choose between quality of food and hunger, or try to cobble together stop-gap measures when the money runs out: soup kitchens, food pantries, friends and families. Based on these statistics, the money could run out as soon as halfway through the month. That’s a lot of improvising.

There had been a push in Congress to index the benefit amount to the price of food in each county, but with the current political climate favoring cutting benefits and limiting how much a household can receive, it appears for the near future, we’re left with a spending gap at best.

I remember dropping off sweet potatoes at a church pantry in central Charlotte one November. A woman visiting the pantry said she was on her way to Matthews, a suburb. She’d heard there was a church there giving away turkeys and she was hoping to get one for her family’s Thanksgiving. She’d be taking the bus, which is, at best, an hour-and-a-half one way. Then, if she was lucky, she’d lug a frozen turkey home on the bus, another hour-and-a-half. (That three-hour bus trip –which cost her more than $4 — would have taken less than an hour in a car.)

I remember dropping off sweet potatoes at a church pantry in central Charlotte one November. A woman visiting the pantry said she was on her way to Matthews, a suburb. She’d heard there was a church there giving away turkeys and she was hoping to get one for her family’s Thanksgiving. She’d be taking the bus, which is, at best, an hour-and-a-half one way. Then, if she was lucky, she’d lug a frozen turkey home on the bus, another hour-and-a-half. (That three-hour bus trip –which cost her more than $4 — would have taken less than an hour in a car.)

If we want people to eat well – and it benefits all of us if people remain healthy, which they cannot do without decent food – we’ll need to figure out a better way to close this gap. If that is a better and expanded food stamp system, then that’s what we need to be asking our representatives for. If it’s a better and expanded food network in communities, then we need to figure out the incentives necessary to make that work for those who provide the food as well as receive it.

Until then, people continue to struggle.

* Jean Blish Siers is the SoSA gleaning coordinator in Charlotte, North Carolina

MAR

2018