by Sandee Gertz *

(originally published in Clarksville Online, used with permission)

Nashville, TN – A tube of toothpaste. A New Testament mini-bible. A can of Old English Malt Liquor beer. That was all I found at the base of trees of the State Capitol lawn where a young man had been lying in the sun without a shirt on for two days in the Nashville heat.

Nashville, TN – A tube of toothpaste. A New Testament mini-bible. A can of Old English Malt Liquor beer. That was all I found at the base of trees of the State Capitol lawn where a young man had been lying in the sun without a shirt on for two days in the Nashville heat.

A cardboard sign was propped up against his tennis shoes: “HUNGRY” was scrawled on it in capital letters—hastily it appeared—in fine point pen.

“You know when everything inside of you is weak…“So numb you don’t want to speak…”

Downtown Nashville has broken my heart a hundred times over with its very obvious hungry and homeless population. Each time I leave my apartment, I’m reminded of despair amidst the dreams of Music City. The need is palpable and the hungry are easy to spot – on Church Street (an orderly hub of panhandling and activity), many are hardened, older, and weathered.

You can give food and dollars, and I do, but it is never enough. It can become overwhelming. Or worse, it can start to seem routine. But something in particular about this young man (he had to be in his early twenties) pulled at my soul for days.

He wasn’t a regular. He seemed too clean, too young—too new to the streets to last long. He looked more like a young musician. I half expected him to rise up and hurl a guitar case on his back, and walk off toward Broadway for a gig. And if he was hungry, why place a sign where few can see it to offer a hand?

“This is just me. Broke down. No roadside assistance…”

Each time I passed him, I was on a run—or walking rather–on my way to my run at Bicentennial Park. He was just to the left of the long massive stairs that lead to Rosa Parks Boulevard. Immediately after seeing him and the sign, I felt inside my armband that holds my phone. Some days, I’d have a few dollars tucked in it for a tomato or squash at the Farmer’s Market, just adjacent to the park. I thought perhaps I could offer to pick up something for him there. But I was empty handed.

I also doubted he’d still be there on my way back; it was nearing 97 degrees and he was completely exposed. But as I felt the burn in my legs winding up on what felt like the hundredth step, I also felt this young man’s eerie gaze. He was sitting up then, knees crossed, as though he were simply soaking up rays on the lawn.

Except his gaze at me was cannibal like. I felt it run through me. My thoughts of wanting to talk to him suddenly turned to hesitancy. I felt at once a strong pull to this young man’s plight as well as an odd sense: a danger.

I couldn’t help but think of my own, grown sons, and how, if they were in this state, I’d certainly want to know. This boy has to have parents, I thought.

“I have callouses on my feet…I’ve just been runnin’ for too long…”

Sandee Gertz, gleaning with SoSA in Nashville

Ironically, later that same day, I would be doing “gleaning” for the Society of St. Andrew’s Hunger Network, right down the steps from this young man. This was why I was in a hurry. I made a mental note that I’d go back after we gathered up the food at the market for the day and took it to the mission.

A close friend of mine, as well as my sons, had been volunteering with SOSA for a few months; it operates with a mission for the hungry and takes its cues from the Bible scripture in Deuteronomy 24:19: “When you reap your harvest in your field and forget a sheaf in the field, you shall not go back to get it; it shall be left for the alien, the orphan, and the widow, so that the LORD your God may bless you in all your undertakings.”

My friend and I had gleaned once at a farm. My sons had gleaned blueberries from the Titans Stadium perimeter. (Yes there are edible berries there.) And I’d just volunteered to be the Bicentennial Farmers’ Market representative who would pass by the stalls each Saturday and take anything donated to the Nashville Rescue Mission. I vowed I would come back to this man. Leave something at the edges of his camp. His hunger and his gaze seemed to be transmitting something to me.

“I know that this is my journey, and though things may hurt me…”

But then I did something terribly human. I forgot. The next morning on my way to my run, I saw him again. Again, I felt for my armband. Again, I had no money. “How could I have forgotten to come back yesterday, I thought to myself,” cursing and making another vow that when I came back up the steps, I’d get to the bottom of his story of sunbathing and hunger. When I jogged to the top, not even an hour later, his frail body was pressed even more lightly into the grass, this time on his side. He had to be literally baking. He couldn’t be spoken to. His pose had the look of someone giving over to something, giving up.

I’ve always been someone who wants to help. I’m the “Cat Rescuer,” the riverfront mom to a feral colony I feel a duty to maintain. I’ve gone into stores before for food for people on the street. I’ve stood and listened, given. But this man, I felt, needed something more. He seemed dehydrated, listless as the leaves that had fallen from the tree that was giving him only partial cover.

And then I made a decision. As I walked away, I called the police. I know. It sounds like the last thing I should’ve done. But I feared for him. In my mind, I wished I could have been the one to right whatever the world’s wrongs had done to him, but in this case, I felt he needed something more, lying as he was in the sun for at least two, perhaps three days unassisted.

I wished at that moment for a male to be with me to talk to him. I didn’t know if he was angry, imbalanced. I was torn: I didn’t want the police to treat him as a criminal—I just wanted him to stop lying in the 95 degree sun, burning with hunger, and reminding me of all the terribly wrong things that can happen in a life: any life. (The familiar scripture: “There but for the grace of God, go I,” repeating in my head…)

The next two days I passed the same spot. He was gone. I felt an emptiness. Did I do the right thing? Was he finally getting help, water, food? I tried to picture him, lined up with people in a shelter, waiting on a plate. I couldn’t see it. I wondered if he fought with the police and said he had a place to go. Did he lie?

Walking back the second day past his abandoned camp, I was drawn to inspect that quiet base of branches and leaves. I don’t mean to sound prophetic, but I had a feeling there was something left for me to find; I had a hunch it would be words. At first, I only saw the toothpaste tube half-empty and squeezed irregularly, the green mini bible splayed out to some page I couldn’t make out. The can of malt liquor was a short ways away and might not have been his. I looked for a notebook. There was nothing.

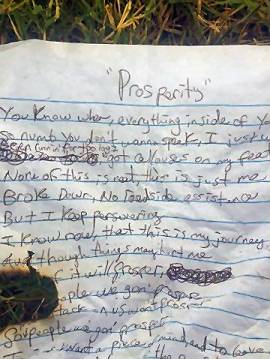

As I walked away, however, on the other side of the trees, I saw a crumpled piece of ruled, white notepaper. I picked it up. It was titled “Prosperity.” It was a poem, or possibly a song, and it contained all the lines throughout this column. As well as these:

As I walked away, however, on the other side of the trees, I saw a crumpled piece of ruled, white notepaper. I picked it up. It was titled “Prosperity.” It was a poem, or possibly a song, and it contained all the lines throughout this column. As well as these:

“But I keep persevering…And we are gon’ prosper…we are gon’ prosper…”

As I read the lines at the beginning conveying the young man’s weakness, I crushed inside a little. On the lines that began to speak about “prosperity,” there was a round burn hole directly through the paper: I knew I really needed to find him. I wanted to tell him that someone cares whether he lies in the sun for days on end not eating. Wanted to tell him that I saw his banana peels rotting in the sun, that I couldn’t forget the look of hunger on his face, and perhaps even just as important: that I had seen his writing. I carefully laid it back underneath the trees in case he came looking for it.

I thought of my own much younger self and the precarious predicaments I got myself into at times. But I always knew in the back of my mind that there was someone to turn to. What could it possibly feel like to know there was no one to listen? I thought also of the beauty of words—how under that tree, hunger gnawing at him—this young man was still drawn to express himself. I thought of how essential and sacred simple words on a page can be.

For two days after, I called the police barracks to no avail; I couldn’t find the right officers on the right shift, and even if I did, I was told they would not be able to give me any pertinent information. I punished myself inside on each run I did for being afraid to speak up, for calling the police when they likely didn’t do anything but push him onward. I stopped a man in uniform walking to the courthouse. He also told me it was nearly impossible to find out what happened. I asked landscapers mowing the state capitol lawn. They’d seen him, yes, but nothing else.

As I walked around downtown, haunted by this young man, I noticed even more despair around me. One night as I walked to feed the river cats with a companion, I thought we were alone, but when I looked closely, I saw people blending quietly into monuments at Public Square Park for a night’s sleep, and two gentleman sleeping sitting up on riverfront benches—still as mannequins—providing a surreal backdrop to the city.

The next day as I walked, I found it strange that in my own defeat to find the boy again that, I too, found it was words that came to me in frustration: language. I started composing a song in my head. It helped.

This month is Hunger Awareness Month. Tennessee ranks sixth in the nation for “food insecurity,” which means that 18% of people do not know with “security” where their next meal will come from. The report found that 18.9 percent of Nashvillians live in poverty — a higher rate than Tennessee (17.9 percent) and the nation (15.9 percent).

More than 39,000 Nashville households try to get by with annual income of less than $15,000 — deep poverty often concentrated in neighborhood pockets in a city with “tremendous” socioeconomic disparities by race, gender and geography, according to the report.

Our city glitters so brightly for our tourists, our wealth and platinum record success is broadcast for all to see. But we must look in the corners to face our increasing and growing needs of hunger and homelessness before they overwhelm our pride in Music City.

I’ve personally witnessed the growth of desperation in just two and a half years living downtown. Community leaders will need to apply further focus and vision to this very raw problem and organizations like the Society for St. Andrew can help with some real solutions for immediate hunger.

As for the young man in this story, I wish I could say I have a better ending. I can say that I did see him again. This time I was walking with my sons and they stayed in the background while I addressed him. This time he was lying under an entire sleeping bag—again in 95 degrees. “Hey, hi. Are you the same guy who’s been here several days? I asked. “I might be. I guess,” he responded. There seemed to be a difference in his tone than what I expected. “Are you hungry?” I asked, insistent.

“I’m not asking you to bring me food, but if you did, I would eat it,” he said.

I spent time waiting in two lines at the Farmer’s Market to get him a toasted deli sandwich, heated, healthy chips, and a brownie thrown in at the last second. And water. It wasn’t a gourmet meal exactly, but hearty. When I got back to him, he had vanished. There was another man there. Pacing. Not asking for anything: no sign.

I asked him about the young man. He’d said that he’d got up and walked away. I said that he was hungry and I had food. The man said “I’m hungry.” He had just gotten out of jail, he told me; he was polite. He told me he was just trying to find a friend on his phone to come and help him get some food. I said the bag in my hand was his. We chatted and I wished him well, gave him some places to go for help and clothes for interviews. I walked away back toward my apartment. It was all I could do. That, and finish the song in my head.

About Sandee Gertz

*Sandee Gertz is an author and award-winning poet from Western Pennsylvania whose work focuses on working class and blue-collar themes. Her book, The Pattern Maker’s Daughter, is available at Amazon and through Bottom Dog Press. Her book-length memoir, Some Girls Have Auras of Bright Colors, (a quirky, coming of age story about growing up with a seizure disorder) is currently making the rounds of literary agents in New York City. She has a Master of Fine Art (MFA) from Wilkes University’s Creative Writing Program and teaches English at Lincoln Technical College in East Nashville. She is currently working on a new novel, and occasionally “poem busks” in Printers Alley in Downtown, Nashville.

*Sandee Gertz is an author and award-winning poet from Western Pennsylvania whose work focuses on working class and blue-collar themes. Her book, The Pattern Maker’s Daughter, is available at Amazon and through Bottom Dog Press. Her book-length memoir, Some Girls Have Auras of Bright Colors, (a quirky, coming of age story about growing up with a seizure disorder) is currently making the rounds of literary agents in New York City. She has a Master of Fine Art (MFA) from Wilkes University’s Creative Writing Program and teaches English at Lincoln Technical College in East Nashville. She is currently working on a new novel, and occasionally “poem busks” in Printers Alley in Downtown, Nashville.

Here are Sandee’s Facebook page and email.

SEP

2015